Early daylight crests the hills and lifts the valley fog. The chill of the early autumn morning has already begun to dissipate with the sun’s return. My family and I amble slowly down the old New York state Route 17 in a three-vehicle parade, the only movement on the otherwise tranquil road.

Old 17 lies in the heart of the Seneca Nations of Indians’ Ohi:yo’ territory. The road connects the municipalities of Salamanca and Steamburg, and runs roughly parallel to the Ohi:yo’, or Allegany River, for which the territory is named. The road has long been closed to general thru traffic, effectively replaced after the construction of the nearby Southern Tier Expressway, Interstate 86, in the 1970s. Decades of neglect have left Old 17 in disrepair. The two-lane road is more pothole than path in some areas.

We’ve been driving no more than 15 minutes, but we may as well be a world away from our home in the center of town. Maples, hickorys, poplars, and a wide array of other flora in varying stages of successional growth abound. The natural baffling provided by the trees obscures the distant hum of traffic on I-86, with birdsong and the creaking of branches in the canopy taking its place. This road, the surrounding woodland, and the oft-exposed riverbed have become a popular locale for four-wheelers over the years. Choruses of all-terrain-vehicle engines occasionally lend a whining, mechanical harmony to the natural soundscape.

Old 17. Footage by Nathan Abrams.

Our little motorcade snakes along Old 17 slowly, trying in vain to avoid the worst of the road damage. My sister and I bring up the rear, while my brother, sister-in-law, niece, and infant nephew ride nestled in the center. We keep our eyes trained ahead on mom’s brake lights while dad surveys the brush from the passenger seat. Somewhere in and among the trees lay the foundation to his childhood home.

In the mid-20th century, Route 17 passed through and connected the Seneca communities of Red House, Shongo, and Jimersontown along with several others. The old New York state Route 280, joining with state Route 17 around Cold Spring (and likewise vacant today), led to Quaker Bridge and beyond to yet more life. Many homes lined the roads all along the way, enclaves of families forming small “neighborhoods.”

Elders today paint an idyllic picture of those times. Steve Gordon, a Seneca elder and former resident of Cold Spring, wrote in his memoir, “Cold Springs: My Home, My Memories, My Story” that, “... there was a feeling of closeness among Seneca families and friends. [...] No one was left to struggle or suffer alone.”

This sense of deeply ingrained kinship is what sustained the people of these communities through hard times.

“It wasn’t an easy life in Cold Spring by any means,” Gordon writes. “However, it did not include much of the stress that came with participating in the so-called, American dream. [...] We did without and there were days when we were cold and hungry, but we managed without tears or regret.”

I can know only what I’ve been told. For half a century, these lands and more along the Ohi:yo’ have been unoccupied by the Seneca people who once called them home. In my lifetime, these once thriving communities have existed only in stories, in the memories handed down by those who knew and loved them.

In the 1960s, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers constructed the Kinzua Dam downriver near Warren, Pa. The dam, completed in 1965, was proposed by the Corps as a means of flood control for the city of Pittsburgh. Though the dam was built miles away from the Ohi:yo’ territory, the resultant reservoir extended into its boundaries, encroaching on and inundating Seneca communities in the southwest of the territory.

The Kinuza Dam under construction. Footage courtesy of Seneca Iroquois National Museum/Onöhsagwë:de’ Cultural Center.

The Seneca people contested this intrusion up to the Supreme Court, ultimately to no avail. Despite protections of sovereign Seneca land ownership under the 1794 Canandaigua Treaty, the federal government ruled in favor of the Corps’ plan. The Seneca Nation of Indians was in effect forced into granting a flowage easement. This meant all lands on Seneca Ohi:yo’ territory below the elevation of 1365’ were condemned. No habitation or permanent structures would be permitted.

Around 10,000 acres, roughly one-third of the Ohi:yo’ territory’s total 30,469 acres, were affected by this ruling. The reservoir completely inundated several communities. Many others remain largely untouched by flooding to this day. However, being below the elevation of 1365’, these communities too were subject to condemnation and compulsory evacuation. This forced the destruction of nine Seneca communities and the displacement of more than 600 Seneca people.

Homes were burned to the ground, bodies exhumed from burial sites — lives and communities uprooted. The reciprocal relationship that sustained the lands and the generations of Senecas who cared for them was drowned out in the interest of sustaining settler industry downstream.

The controlled flood completely inundated several communities. Footage courtesy of Seneca Iroquois National Museum/Onöhsagwë:de’ Cultural Center.

Though the lands have been condemned, much of the area remains accessible. People can visit and often do, with many younger Senecas coming to the areas around Old 17 and state Route 280 for all manner of recreation, such as camping, kayaking, fishing, and hunting. The old communities are indeed sites of abundant natural beauty on the territory.

It can be harder, however, for survivors — children at the time of the relocation but elders today — to return to the places they once called home. As Gordon writes in his memoir, it is not only the changes to the landscape, but the pain and weight of loss that makes these return trips hard to manage.

“Many times I’ve gone back to the physical location of the old home; it’s all overgrown with fifty years of brush and trees,” he wrote. “I’ve weeded my way through the briars to the area where a few large stones lay half-buried, stones that once served as the foundation, and I’ve stood quietly. For that moment, I stood in anticipation of any sound or whisper that says, ‘welcome home.’ Generally there is only the chirp of a sparrow or the wind in the nearby poplar trees.”

My father has not been back on the site of his old childhood home since he left nearly 60 years ago. In September 2020, my brother and sister-in-law suggested that we all take a trip down Old 17 to visit the old property. They had just welcomed their son into the world three months prior. After a summer separated by pandemic travel restrictions, they felt their son’s homecoming would not be complete without a proper introduction to his family history. Saturday morning, rising and moving west with the sun, we set out for dad’s old homestead.

We’ve been traveling single file through the woodland for some time now. When my dad signals, we park along the roadside and continue the search on foot. We walk up and down the road slowly while he sorts out exactly where in the brush his old home had been. My dad grew up here, but he also has decades of surveying experience as the director of the Seneca Nation of Indian’s Maps and Boundaries Department. He possesses a more intimate knowledge of these lands than most. In no time, he identifies a stand of trees marking the old property.

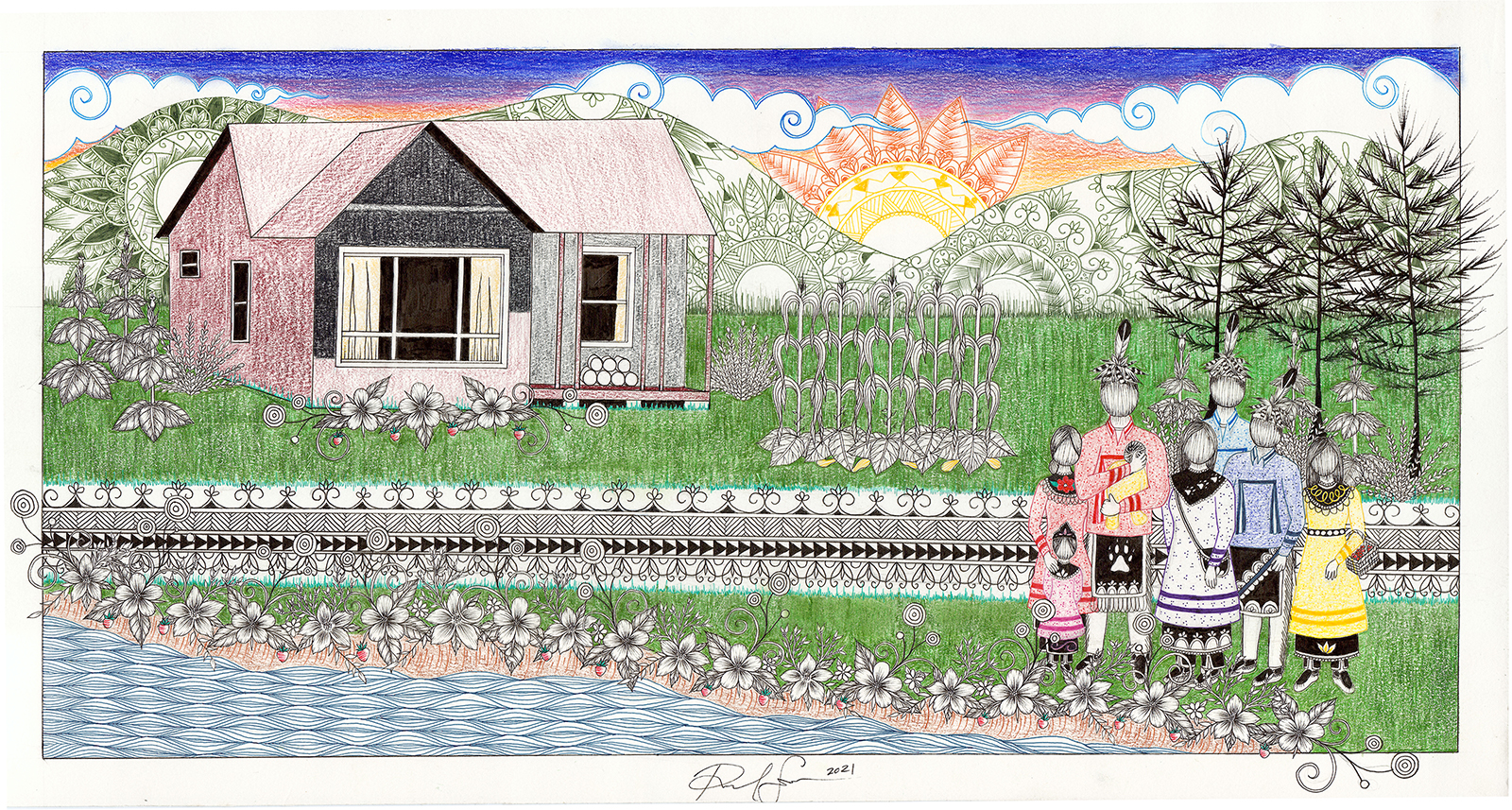

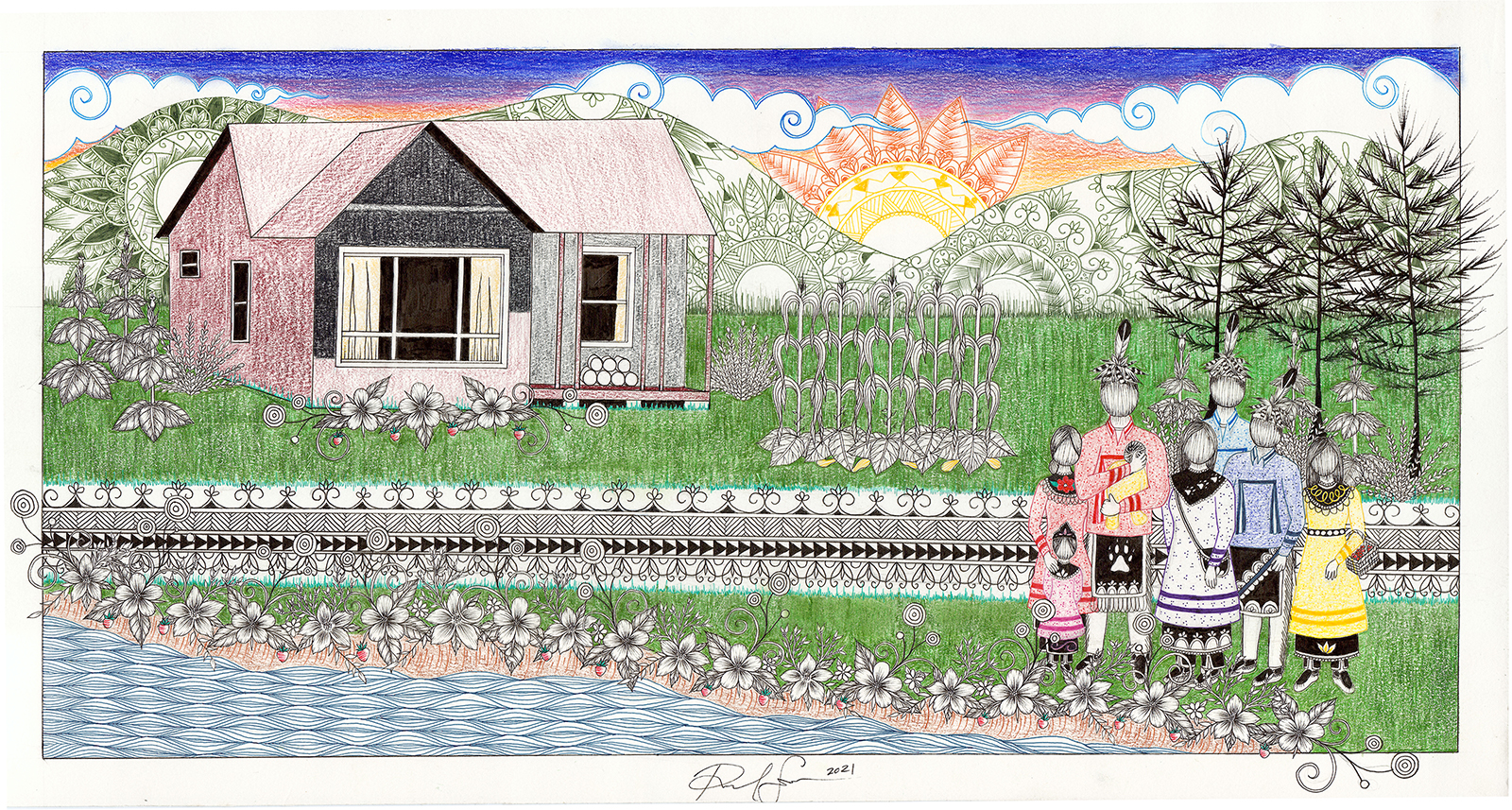

Our first family photo since the birth of my brother’s son in June 2020. Photo courtesy of Caleb Abrams.

He also points out the area where his great-grandmother Jenny Huff lived next door. A modest garden plot lay between their homes. My dad recalls tending to her crops of corn, beans, and squash alongside his brothers, his parents, and Jenny’s other grandchildren. Jenny, for her part, kept the canning jars and pickle barrels in her root cellar stocked with their yield. My dad tells me these preserves were much of what they ate in the winter months.

My grandmother Rovena Abrams also grew up working alongside her siblings on a comparatively larger plot at her childhood home in Coldspring. In addition to a large crop of staples, such as corn and potatoes, they also kept cows, chickens, and a workhorse named Buster. She continued taking care of her parents and their lands even after moving down Route 17 to the edge of Redhouse, bringing her boys along to help.

This was how many people sustained themselves before the Kinzua Dam was built. Families remained close and looked after one another. When the dam was built, households were relocated to one of two planned communities, Jimersontown to the east and Steamburg to the west. These sorts of family-sustained agriculture declined in the resettlement communities.

The allotted acreages on the resettlement properties were often smaller than many families lived on previously. Households such as my grandmother’s childhood home, with vast fields and a barn full of livestock, could not simply pick up and move to another, smaller location. Households were also shuffled around in the relocation process. Pre-removal, families could live beside and support one another, as was the case with my dad and his great-grandmother. Separated by many roads and miles, these relationships of care became harder to maintain.

The relocation was not a simple change of address. It disrupted or destroyed the lifestyles of Seneca people in myriad ways. Dr. Randy John, a Seneca elder and sociologist, has published several works on the culture and history of Seneca people, specifically at Ohi:yo’. Dr. John was one of a minority of Senecas at Ohi:yo’ living outside of the 1365’ floodplain at the time of the dam’s construction. He was not displaced, but he grew up knowing a similar way of life as my father and other survivors. For his first book, Dr. John interviewed elders from Ohi:yo’ on their experiences before and after the removal. Dr. John points to the rapid shift from rural living to a more conventionally settler-American way of life as being an overwhelmingly disruptive paradigm shift for the community at large.

Footage by Nathan Abrams.

“We had to survive by hauling water, chopping wood, and ... when you get thrown into a middle-class home like that, now you have to work,” Dr. John says. “You have to live differently to meet your basic needs. Because you are forced to leave your lifestyle, on your own land, and your own homes were burnt by the government.”

This compulsory assimilation into “mainstream” American life was an intended consequence of the relocation. The Kinzua project must be understood in the context of the era. In her book, “The Allegany Senecas and the Kinzua Dam: Forced Relocation Through Two Generations,” Joy A. Bilharz points out that U.S. federal policy at the time, “emphasized termination of the relationship between tribes and the national government.” Termination era policies were purposeful legislative efforts designed to stamp out Indigenous self-determination and sovereignty and to subsume Indigenous peoples into the “mainstream” American population at large. As Bilharz puts it, “Assimilation was the order of the day.”

Section 18 of the Kinzua Dam Act (Public Law 88-533) specifically calls for the termination of the SNI’s federal recognition by August 31, 1967, scarcely three years after most Ohi:yo’ communities had been uprooted. The SNI managed to fend off this edict until U.S. President Richard Nixon ended the U.S. policy of termination in 1970. This, however, did not undo the cultural and social damages wrought by forced displacement. “For our way of life to separate the elders from the children, and the children from the elders, and the elders from their immediate family, it was not a positive force for social integration,” Dr. John says. “This certainly had a cultural impact upon us if you simply think about what happened with language. […] The moment that you took those elders away from their adult children and their grandchildren is the moment that you took them away from being first language speakers.”

The cultural loss extended beyond language. “It was damaging to the connections we had to our traditional paths,” he says. “It didn’t destroy it, but it certainly did not strengthen it.”

Despite these attacks, Seneca culture continues to thrive at Ohi:yo’. Longhouse ceremonies continue. Elders pass down language and cultural knowledge via dedicated programs and departments of the SNI. Even agriculture has returned to the old lands. The SNI’s Gakwi:yo:h Farms moved their bison herd and a crop of white corn down to the area of Sunfish on Old 17, restoring life and a relationship of care to the land. “We are survivors,” Dr. John says. “Senecas are very adaptable. We’ve had to adapt numerous times.”

At the far edge of my great-great-grandmother’s property, a dirt path cuts back from the road and into the woods. My dad tells me this was a wagon trail even before his youth, though the wide tire tracks in the mud indicate that four-wheelers are the preferred mode of transportation today. The decades of growth over dad’s old homestead make it hard to see much from the road. We decide to follow the path from Jenny’s home in search of a new perspective.

A short way down the line, we arrive at a wide pond tucked away in a clearing among the trees. Belying its picturesque beauty, still and glistening with midday sun, the pond is an old gravel pit from the time of Route 17’s construction, filled in over the years by the river. This is where my dad learned to swim and where his father taught him and his brother how to fish. In the years since the relocation, my dad has returned on occasion to the roadside of his old home, but he hasn’t ventured this far back in those intervening years.

When he was young, my dad used to make this same walk with his father to check traps they’d set down on the riverbanks. Grandpa used to trap for muskrat, processing the hides at home, and selling them out in Cherry Creek, N.Y. to supplement the family income. After the relocation, the two stopped trapping. Distance from the river, more hours spent working for primary income, and a general apathy following their circumstances conspired to take away this activity from father and son.

My father hasn’t been back to this side of the river in over 50 years. Courtesy of Caleb Abrams.

For the many Senecas who relied on the river ecosystem for sustenance and survival, the ecological damages that the dam wrought upended their way of life. It was not only the people, but also the nonhuman residents along the river whose homes and lives were destroyed without warning or consent.

The unnatural ebb and flow of damming has led to environmental degradations in the reservoir areas along the Ohi:yo’. Unseasonably shallow waters become overheated, causing harmful algal blooms of cyanobacteria. This makes the waters toxic for humans and forces fish to seek colder waters away from SNI territory. The dam also disrupted or untenably altered the natural reproductive cycles for flora and fauna. The paddlefish, hellbender salamander, and rayed bean mussel are all classified as critically endangered today.

Dr. Jason Corwin, executive director of the SNI Media & Communications Center and member of both the SNI’s Watershed Resources Working Group and Climate Change Task Force, does not see the Kinzua project as an isolated incident. Rather, it is but one in a long and violent history of U.S. government-backed public works projects which have explicitly targeted Indigenous peoples and lands. “That’s kind of part and parcel of the colonial project,” Dr. Corwin says. “All negative [environmental impacts] get placed on the disenfranchised and politically less powerful, and the politically powerful reap all the benefits.”

Dr. Corwin has produced several documentary films in recent years following Indigenous resistance efforts to such projects, specifically those concerning water protections. “Denying Access: NoDAPL to NoNAPL” links the struggles against the Dakota Access Pipeline at Standing Rock to that against the Northern Access Pipeline around Seneca territory in western New York between 2016 and 2017. “Defending Ohi:yo’” follows the successful community campaign in 2018 against a proposed fracking wastewater dump at the headwaters of the Ohi:yo’. “Sadly it is an often repeated situation,” Dr. Corwin says. “I think maybe what was particularly unique was that, in this case, a fully workable alternate plan was presented.”

As part of their broad mobilization against the Kinzua project, the SNI recruited hydrologist Arthur Morgan to devise an alternate plan that would not impinge on treaty protected territory. Morgan was a nationally-renowned drainage control expert who had previously worked with the Army Corps of Engineers as the former chair of the Tennessee Valley Authority. The so-called “Morgan Plan” would have diverted reservoir waters from the SNI Ohi:yo’ territory north into the Conewango Valley, with excess eventually spilling into Lake Erie.

This plan, rejected by the Corps as unfeasible, would have forced the displacement of non-Indigenous residents within its floodplain, though far fewer than those at Ohi:yo’ and not in violation of one of the U.S.’s oldest standing treaties. Again, the context of the time must be taken into consideration. The Kinzua project’s termination era conception took Indigenous disenfranchisement as a virtue — not an oversight. “It was a very sensible alternative,” Dr. Corwin says, “but they wouldn’t accept it because, my suspicion is, [the Corps] thinks it’s better to inconvenience and negatively impact a whole bunch of natives than it is to do it to a small amount of white people at the end of the day.”

As Dr. Corwin’s recent documentary work demonstrates, the SNI and the Ohi:yo’ watershed face continued attacks from shortsighted settler industry. We remain as water protectors not only for ourselves, but for the health and safety of all. It is in everyone’s best interest to remember the history of the Kinzua era and to pass it along to future generations.

Dad shares stories freely as they return to him along our walk. We press on further into the thicket, gradually stratifying as we go; the lineup of our early morning parade reshuffled. My mom and I walk leisurely behind the rest, stopping often to observe the abundant sunlight filtering through the canopy. My sister, carrying our nephew on their first walk together, accompanies our brother and sister-in-law a short way ahead of us. The intrepid duo of my dad and my niece lead the pack.

We march along, propelled forward in equal measure by my niece’s eager curiosity and my father’s unfurling memories; one unconsciously intent on the experience of abounding newness, the other revelling in the reminiscence of bygone days. To see generations walking together in one of the old communities is, to my fortune and gratitude, a comforting and familiar sight to me.

In 1984, the SNI declared the last Saturday of every September to be Remember The Removal Day. Thereafter, the day is recognized with programming which seeks to honor the memories of those we’ve lost and to educate those who do not know their stories. My parents have ensured that our family attends every year.

The day begins in one of the communities vacated by the dam’s construction. After words from elders and community leaders, those who can begin a walk back to one of our community centers. The youngest among us may only feel the excitement of moving as a slow parade through the forest. The elders may carry both comfort and sorrow, all along the way feeling the presence of people and places they’ve known and loved.

Covid-19 safety protocols necessitated that RTR Day look different this past year. Instead of the usual communal gathering, families were encouraged to visit any one of the old communities they had a personal connection with to reflect and share stories. Everyone would make their remembrance in their own time and way.

My father used to walk this path to the river with his father to check his muskrat traps. On this day, my niece led the way. Courtesy of Caleb Abrams.

My brother’s family’s visit coincides with RTR Day this year. Our trip then holds a meaning and presence beyond our small group. As we walk, feel, and remember, we do so in the echoed presence of those many years and people with whom we have done so in the past.

RTR Day has always been a bittersweet day of reunion in the community. Though we come together in commemoration of a moment of tragedy, we gather to share in grief and healing. Rebecca Bowen, a dear friend of my mother’s, is always a friendly face among many. Bowen is a relocation survivor and one of the original members of the first RTR Day planning committee in 1984. She has seen RTR Day shift over the years as the history is passed down among generations. “The first one was 20 years after the relocation, and memories... and all those things were kind of fresh, so it was really a somber day,” Bowen says. “Nowadays, it’s not so much like that.”

In the years since the first RTR, the focus has necessarily shifted to education and awareness as survivors have passed on.

“It’s natural, you know, I guess, when you really think about it,” she says. “We’re looking at a lot of years ago now — 60 years — so I guess it’s to be expected. I was a child during Kinzua, and now I’m a grandmother. Almost that entire generation that was older than us, they’re almost all gone now. Our parents, our grandparents, the elders of those days. Now, the children of Kinzua are the elders.”

Bowen has dedicated much of her life to ensuring that the past and present stories of the Seneca people be told and preserved for future generations. She serves as the director of the SNI’s Archives Department, with nearly two decades of experience in that office. She became a family friend by way of her work as co-editor of an independent community newsletter, The Orator (“The Native American Voice”), alongside my mother. In all, she has worked to ensure that Seneca stories be preserved by and for Seneca people.

“You have to live differently to meet your basic needs. Because you are forced to leave your lifestyle, on your own land, and your own homes were burnt by the government.”

“We need to be sure that this will be carried on, every effort has to be made to keep up that work,” Bowen says. “We’ve lost a lot through the years. We have a lot of pieces of the puzzle that are missing, and they sure would be great to have. And they’re missing because they didn’t have a home.”

Stories can only find a home only when they are shared. My brother and sister-in-law wanted to be certain that their son, from his earliest moments in this world, was familiar with a place and story that have made our family what it is today. The lands where his grandfather lived will know him, and he will carry their memory.

I’ve walked many times on these lands between the exuberant innocence of children and the solemn reflection of elders. Always there is something which is felt but incommunicable between generations. I never can truly know the joy and pain of life and loss that survivors carry, but I still hold all that has been handed down to me. Seeing the eldest and youngest of our family bound ahead down this path, I feel myself, as ever and as us all, at the confluence of the years.

We come to the end of the path. The dense greenery gives way to open air and a bright blue sky. The exposed riverbed stretches out, a wide expanse of alluvial soil and smooth stones. At its distant edge, the Ohi:yo’ flows in a mere trickle. Across the water, I-86 looms high on a concrete embankment against a hill. The dull, shrill hum of the many tires, carried by the valley’s wide echo chamber and no longer obscured by brush, comes to the forefront.

My dad tells me that this is what the river looked like before the dam was built and the water level artificially swelled. This is the first time he’s made the walk from his old home to the river since the Kinzua Dam forced his family’s displacement almost 60 years ago. On the day of his return, he sees the Ohi:yo’ flowing familiarly at the far side of an unstable, unnavigable terrain: clear in his field of vision but just out of his reach, a distant reflection of the river he knew in his youth.

My dad, carrying deeply woven memories and stories of this place, stands at the forest edge holding his grandson in his arms. My nephew, feeling and coming to know the world in a new way every day, rests in the arms of a family and home that will always know and welcome him.

After summer months, reservoir water levels are lowered to pre-dam elevations. This exposed riverbed was previously lush woodland. Courtesy of Caleb Abrams.

I trudge across the alternately doughy and craggy terrain with my niece down to the current and erstwhile river bank. Our presence feels significant, something like a homecoming, though I still feel a distinct distance. Despite hearing stories from my dad and standing now in a space practically reflective of the pre-removal landscape, I am unable to grasp the totality of what was lost and what is missing. An intractable gap lays between my father and me: no more than 200 feet and no fewer than several lifetimes.

The years eventually keep us at a distance from the places and stories we’ve known. We may stand on the banks where movement recedes into old growth and watch those who’ve come behind us walk on ahead. We may stand between generations, lifetimes, and caretakers. Something quiet, cool, and growing may stand invitingly, comfortingly behind us. Something shifting and flowing, evermoving in defiance of what artificial constructions oppose it, may become our distant horizon.

We may return to a place we’ve never in our hearts really left. We may see that those after us might catch, in abstracted fragments, notions of what lies deeply inexpressible in our hearts. We may take solace that they will know and be known, that we can do our best only to share what we ourselves know. We may share and build the totality of our lives as one another’s.

I stand at the water’s edge with my niece. I watch the river flow over the many stones worn smooth by the years. I watch her carry these rocks as we walk and toss them into the stream at haphazard or perfectly precise angles. I can no better predict the ripples than she can. The stream flows on.

We walk along the water together with the current. Our family watches over us from the liminal space between movement and stillness on our distant horizon. My niece takes my hand and leads the way.

Our pursuit of outdoor joy is remiss without the acknowledgement of the occupation of unceded Indigenous land. We are students and journalists working, writing, and living on the land of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, comprising the Six Nations made up of the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora nations. However, acknowledgement is not enough. Read More.