In a climbing gym in Queens, N.Y., Marjana Tafader trained for more than a year in 2019 before tackling High Exposure, a route located in the Shawangunks Mountains (also known as “the Gunks”) on the SouthEast side of New York. That first tackle of the range took her from morning when she set out to the ridge to dusk when she reached the top of the cliff. The experience filled her with pride and gave her bragging rights. Though Tafader is known as the skinniest in her family, even admitting she can appear “fragile” and “weak,” that climb and the ones that followed afforded her the perfect retort when her brothers begin to tease: “Well, I can climb a mountain, can you?”

But tackling the 250-foot mountain delivered many challenges, ones she navigated by herself. When she needed a boost to reach the second ledge, for example, she inched herself up the gray-scale rock on her own. And the times when Tafader felt tired or frustrated with what to do next, she remembered what her mentor told her to do: breathe. “What makes you a stronger and better climber is when you take a moment and take a deep breath. It relaxes your body and you'll feel much stronger,” Tafader says, noting that struggling against the rock only creates a more anxious, exhaustive climb.

"I would never climb a route that had a racist or oppressive name."

When she reached the top, Tafader’s hands were sweaty and covered in chalk. She stared at the sky, a scream of lilac, as the sun dipped beneath the lush August trees. That moment and that climb imbued this place with great meaning for Tafader. “Climbing in the Gunks feels like it has been home,” she says. “It will always be home.”

And that sense of home is something she seeks to build for other women. Since taking up the sport, Tafader has become a mentor for Young Women Who Crush, the same organization that introduced her to the sport and that provides opportunities for high-school girls to start climbing in New York City. But it’s not just the sport she seeks to make more inclusive. It’s the climbing spots, too. While the Shawangunks may serve as Tafader’s oasis and home, it reflects some of the sports’ culture that make it an unwelcoming spot for women and people of color.

Because the Gunks features a practice common in climbing communities, one that reflects the sport’s white, cisgender history. In the past, a climber looking to find a route in the Shawangunks would encounter names that featured female anatomy such as the Land of Pussification or ones that reflected blatant misogyny such as Bitchy Virgin. But those route names are changing — to the Land of Wesification and Brave Valkyrie, respectively. For Tafader, she avoids climbing oppressive routes when navigating in the Gunks. “I would never climb a route that had a racist or oppressive name. I can't be proud of myself saying, ‘Oh, I climbed this hard climb but it had this name,’” she says.

And what’s happening in the Gunks is happening across the country. Opressive route names with racist, sexist and homophobic references have been printed in guidebooks for decades. On guidebook sites, climbers have submitted discriminatory route names for years. In New York, names such as “Little Mexican” or “No Homo'' were titles for routes in guidebook Manhattan on the Rocks, and have since been renamed. In August of 2020, Mountain Project, one of the largest online guidebook resources — with more than 245,000 routes worldwide — announced they had redacted 700 names they deemed “overtly discriminatory.” Since 2020, more than 6,000 names have been flagged by Mountain Project users as offensive and derogatory with 164 routes renamed on the site as of April 2021.

The debate of removing oppressive route names (particularly ones that feature overtly racist and misogynistic language) has been a point of discussion for years as more climbers reckon with the sport’s male, white-dominated culture. Although the sport became more popular in recent years thanks to the boom of indoor climbing gyms, outdoor climbing as a whole still maintains a largely male, white identity. According to a 2019 report conducted by The American Alpine Club, with partnership of more than a dozen supporting organizations, 67% of outdoor rock climbing were white males.

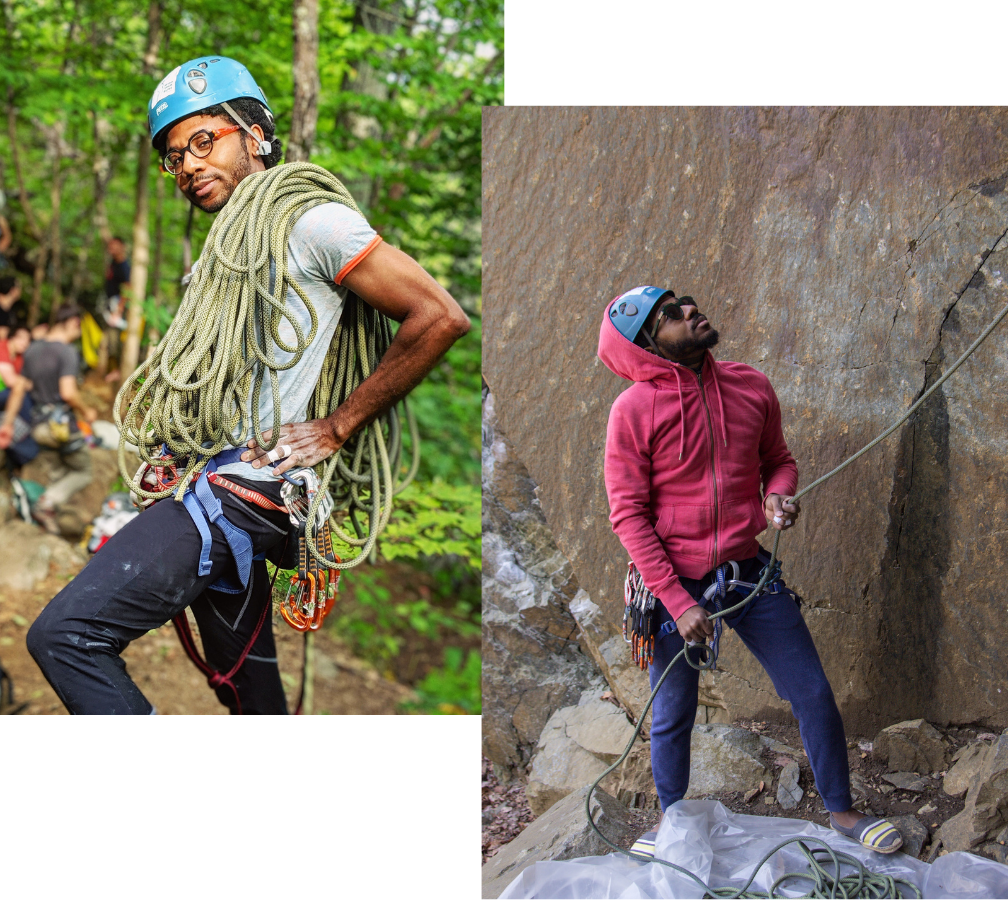

Julian Andrews, president of CRUX Climbing, says that if guidebook authors want to include context on why a route was changed, it may serve as an educational tool for others not exposed to diverse ways of thinking. Courtesy of Julian Andrews.

But the 2020 summer of civil unrest, which was sparked by the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent growth of the Black Lives Matter Movement, helped fuel the movement to make climbing more inclusive. Christian Fracchia, guidebook author and president of the Gunks App, an app that includes more than 800 routes documented in the Shawangunk Mountains, says these events moved the matters of racism and representation to the forefront within the community.

“People were saying, ‘this is it. This is the time,’” Fracchia says. “Let's stop talking about it. And let's do it.”

And now some change is happening. Since last year, Fracchia has edited more than 30 route names. Blatant offenders such as “Kitty Porn,” a route based in Minnewaska State Park Preserve, proved easy. He reached out to guide book authors to request the change, and in most cases, they agreed, shortening the names or eliminating the oppressive attribute. Fracchia says he wants his app to be welcoming to everyone, especially since he also has to uphold the regulations that the Apple and Google App Stores hold them to. Currently, the app is advertised for ages 12 and up.

But other names proved to be a bit more challenging, Fracchia says. For those, he took more time to consider. “Shockley’s Ceiling,” for example, is an iconic Gunks route; the first ascent occurred in 1953, according to Mountain Project. While the name itself doesn’t allude to explicit racism, the first ascensionist, William Schockley, for whom the route references, is known for his racist beliefs and views. Shockley spent the latter part of his career as a physicist trying to prove that Black Americans were part of a “retrogressive evolution” and ultimately was denounced by the scientific community. Rather than Fracchia, who is a white man, unilaterally changing the name, he and Alexis Krauss, the co-founder of Young Women Who Crush, organized an open forum on Zoom inviting Tafader and other BIPOC climbers to discuss the contested name last year. The group ultimately agreed for a name change. Now, Fracchia’s app refers to the route as “The Ceiling” as its first reference but incorporates “aka ‘Shockley’s Ceiling’” in the app. The Mountain Project updated the name and only refers to it as “The Ceiling.”

Julian Andrews, a climber based in Brooklyn, New York, has been climbing for 10 years and travels across the country to places like Red Rocks, Nevada in search of climbing routes. Courtesy of Julian Andrews.

“It's important that we change those names, and we don't perpetrate that kind of racism or misogynistic viewpoints. It's still a work in progress,” Tafader says.

That work continues to spread. Jim Lawyer, co-author of Adirondack Rock, a guidebook with more than 3,000 routes inside Adirondack Park located in Upstate New York, has changed 12 route names that he deemed “unquestionably discriminatory,” on his same-titled guide site. Lawyer and co-author Jeremy Hass have identified 110 names undergoing review, leveraging this protocol to guide his work: “If you have to explain why something questionable isn’t discriminatory, then it needs to be changed.”

Fracchia’s latest guidebook, Gunks Climbing, will include the updated names. Since reviewing, Lawyer has released two mini-guide books in the Gunks Apps that map two Southern Adirondack cliffs with updated name changes. Going forward, these name changes will be reflected on printed publications, he adds.

Fracchia says he has seen local climbers open to name changes, especially if they are harmful to a minority community. According to a survey conducted by The American Alpine Club in February 2021, more than 77% of respondents, who are climbers, agreed it is important to “address discriminatory route names to make climbing more welcoming to all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, national origin, age, range of abilities, sexual orientation, or gender identity.”

Marjana Tafadar started rock climbing through the organization Girls Who Climb in high school. Now, she's mentoring new climbers through the program, teaching them the ins and outs of trad climbing. Courtesy of Marjana Tafadar.

But climbers who are against route renaming often counter argue that the process erases a part of climbing history. Chris Vultaggio, a climber and board member of the Gunks Climbers’ Coalition, a climbing advocacy group in Shawangunk Ridge and surrounding areas, disagrees with that stance. He says the counter argument of erasing history perpetuates an “us-versus-them'' mentality between experienced, hyperlocal climbers and climbers who may be beginners to the sport and may not know how to navigate the outdoors. He adds that, especially for minority climbers who are relatively new to outdoor climbing, routes that incorporate racial slurs could create more isolation. “They’re now going to look at us, as a community, and say, ‘best case we’re tolerant of racism and worst case, we’re just a bunch of racists,’” Vultaggio says.

In regards to the GCC’s role, they can serve as liaisons between their members, land managers and guidebook authors in their community. Vultaggio adds that they are looking to include more ways they can feature and support groups like CRUX Climbing, a nonprofit rock climbing organization that aims to expand accessibility to the LGBTQ+ community.

Julian Andrews, president of CRUX Climbing, sees these deflections of rewriting history as a method of maintaining a status quo rooted in white supremacy. He adds that if guidebook authors want to include context on why a route was changed, it may serve as an educational tool for others not exposed to diverse ways of thinking and identities to understand the revision.

But oppressive route names exist as one factor that contributes to minority climbing communities feeling unwelcome. Climbers echoed that in many ways, route names are just the touchstone for inequities that hinder access to the outdoors. Beyond creating closer ties with organizations that serve minority groups, the GCC has also incorporated diversity initiatives like an annual Justice, Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion framework, known as JEDI, as a way to educate its members on diversity and inclusiveness in the climbing community.

The GCC is also working with Angela Lee, president of Colorado’s San Luis Valley Climbers Alliance, to create a national pledge for local climbing organizations to take a firm stance on route renaming. While the initiative is at the grassroots level, Lee hopes to have the project ready soojn. For LCOs that do sign-on, the pledge also requires them to periodically continue diversity, equity and inclusion efforts to ensure accountability but also weed out those who may see this as only a performative gesture, Lee adds.

Climbers who are against route renaming often counter argue that the process erases a part of climbing history.

For Marian Perez, a mentor for Young Women Who Crush, bridging the gap for those who lack access to outdoor space and educating people on how to navigate within it is the key to bringing more diversity to the sport. When Perez began transitioning five years ago from a climbing gym to an actual mountain face, reaching the outdoors from the Bronx along with finding mentorship cost a great deal. In fact, Perez took out a loan out from her 401K to support their commitment to the sport. Now, she is working to build an outdoor collective that brings accessibility, mentorship, and resources to minority groups under a new organization, Rise Outside, which provides a space for minority groups but also serves as a tool to advocate on issues such as route renaming. By bringing more diversity to the outdoors, she hopes that others can achieve the same mental health benefits she's gained since starting.

Marian Perez says one of the major hurdles in transitioning gym climbers into the outdoors is having quality mentorship. With the launch of program Rise Outside, they plan to mentor new climbers and teach them how to recreate sustainability. Courtesy of Marian Perez.

“When you finish a route and you look out and see all that open space and you're like ‘I'm so small compared to everything else that's around here,’” Perez says. “At least in that moment, I’m O.K.”

CRUX Climbing’s Andrews feels that same tranquility when he’s climbing up a rock like the ant he imagines himself as. He escapes the taxing noise of Brooklyn, N. Y. — the humming of the HVAC system or sirens from the streets — and for a moment, an hour, an afternoon, focuses on the climb and pushes the social-justice issues in his mind to the side. “You're not fighting anything else, it's just you and your ability,” he says. “You have that option of making it like a challenge or you have this option of merging with nature, being part of the atmosphere, having that ability to be something outside of yourself.”

Our pursuit of outdoor joy is remiss without the acknowledgement of the occupation of unceded Indigenous land. We are students and journalists working, writing, and living on the land of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, comprising the Six Nations made up of the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora nations. However, acknowledgement is not enough. Read More.